SOUPS 2017 conference

What I learned while attending SOUPS

This week, I went to the thirteenth annual Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS).

This was possible thanks to a travel allowance offered as part of my internship through Outreachy.

I was not sure what to expect, but what I found was a couple hundred people, mostly in academia, sharing the results of their usability research in the digital privacy and security space. Slides and videos of the sessions will be posted here as they become available.

TIL: SOUPS was originally started at Carnegie Mellon University, and it retains close ties today.

Talks on Behavior

Weighing Context and Trade-offs: How Suburban Adults Selected Their Online Security Posture, presented by Scott Ruoti

Here is the original paper.

Study Details

Ruoti’s team interviewed suburban, middle-aged parents in the U.S., asking them about a number of cybersecurity topics.

Participants’ Perception of Cybersecurity

In General

Overall, these individuals felt that:

- The internet was transformational, and

- News reports made them feel that nothing could be 100% safe online

Threat Model

They learned about threats through the media (news, TV, movies, radio). The top threats they perceived were:

- malware and phishing attacks

- inappropriate content

- permanence of data

- They worried that the stupid things their kids might do or say online would follow them later in life

Impact of Threats

They felt the major impact was inconvenience: how long it would take to recover from an attack. For example, if the attack were from malware, they might need to reformat their PC or install anti-virus software.

They tended to minimize what they felt the impact was, and said there were services available that would fix the problem.

Coping Strategies

Most people opted for a low-cost, high impact solution. Not surprisingly, their position was carefully tied to their perceived impact of the threats: for some that meant taking no action, for others, that meant teaching their children personal responsibility.

Understanding of Cybersecurity Concepts

- Encryption

- About 2/3 of people understood that encryption protects data from unauthorized parties.

- Most did not understand that attackers get around encryption by spying on data before it gets encrypted, not by breaking encrypted data.

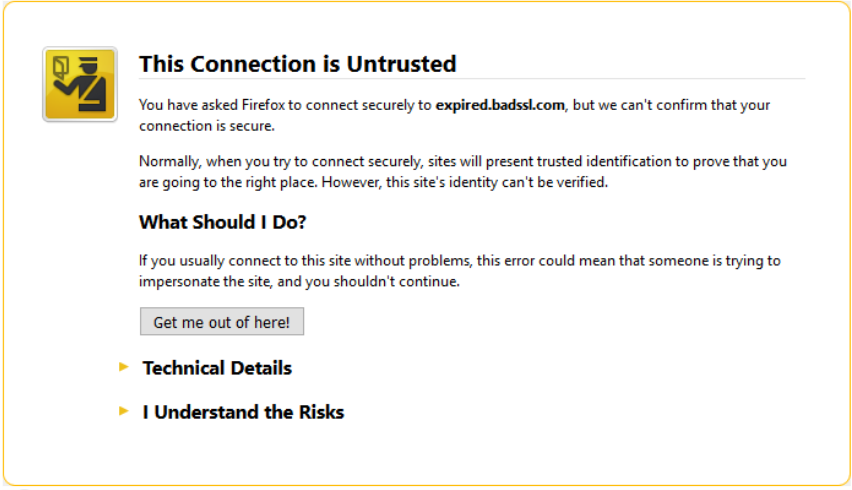

- TLS Security Indicators

- Some people thought that the TLS indicators (such as the HTTPS lock icon in the browser URL bar) indicated site safety, not connection security. This led some of them to ignore TLS warning pages.

- One risk with this misunderstanding, per Ruoti is:

“Phish- ers could take advantage of users trust in the lock icon by transmitting their phishing websites over TLS, leading users to be more likely believe that the website is legitimate and safe.”

Takeaways

In light of his observation that most of the people in his team’s study took a rational, economic (cost-benefit analysis) approach to protecting themselves online, Ruoti makes the recommendation to offer people low-cost, high-impact solutions.

One specific recommendation was about teaching children about cybersecurity, since more and more children are online at younger and younger ages (for example: playing a game on a tablet).

Many parents said their children use YouTube a lot, so one option could be to make whiteboarding videos to explain these ostensibly dry but important cybersecurity concepts.

How Effective is Anti-Phishing Training for Children?, presented by Elmer Lastdrager

Here is the original paper.

Study Details

Lastdrager’s study looked at the effect of a 40-minute cybersecurity training session on 350 children, ages 9 - 12 from 6 different schools in the Netherlands.

The training was storytelling-based, and included training on phishing, hacking, cyberbullying and identity theft.

The phishing training included how to find the URL and sender’s e-mail address in a phishing email, spot spelling mistakes and find urgency queues (for example: “You must respond within 24 hours!”).

Lastdrager’s team looked at six variables:

- Gender

- Age

- Whether the child had their own e-mail address

- Whether the child had their own Facebook account

- Whether the child had reported to have seen a phishing e-mail before.

Takeaways

Children are very active online. Of the 350 children, ages 9 - 12 in the study, 80% had their own e-mail address and 27% had their own Facebook accounts.

Gender did not play a role in the effectiveness of the training. However, older kids did better, as did those with their own e-mail address and/or Facebook account. Whether or not the child had seen a phishing e-mail before did not have an influence.

Lastdrager’s advice for doing any kind of research with children:

- Don’t call it an experiment! He used the term “cybersecurity training”.

- Don’t use overly technical terms. In his case, the word “phishing” was never used. Rather, he just asked “What would you do with this e-mail? Reply, delete, etc.”

- If you’re doing a training, provide it to the control group after the study has concluded.

The importance of visibility for folk theories of sensor data, presented by Emilee Rader

Here is the original paper.

Study Details

The study interviewed non-experts (of technology or quantified self, 80% were women, ages 23 - 48) using the “free list” elicitation technique:

- “Name as many examples as you can of info that an activity tracker knows.”

- “Can you tell me how you think it knows X?”

What are folk theories?

- Theories formed out of everyday experience with technology.

Takeaways

Data on Fitbit’s UI are estimates. For example, clapping can increase a user’s number of steps taken.

People can’t make informed decisions when they don’t even know what is possible. For example, a guy noticed his wife’s fitbit had 10 hours of high heart rate activity. He posted the data to reddit, and it was discovered that she was pregnant!

Very few people were aware that information not directly related to their physical activity could be obtained.

Lightning Talks

Improving Second Factor Authentication Challenges to Help Protect Facebook account owners, presented by Oleg Iaroshevych

Facebook has a password policy for casual users to detect login attempts from a safe or unsafe location. If the location is unsafe, the user must confirm their identity before they can login.

To confirm their identity, the user is given an authentication challenge: they must identify people they have messaged in Facebook.

Design questions for creating this challenge:

- How many people are eligible for this challenge?

- How many options should be shown?

- Should any incorrect entries be allowed?

- Should valid answers be restricted to a date window?

Studies were performed to find the best combination of these parameters.

If the user fails the challenge, they have an opportunity to complete another challenge, such as entering a code sent to the user’s phone.

This SFA change is designed to improve not just actual but perceived security – we want Facebook users to feel safe when using Facebook.

By Facebook measures, this change was a success:

- 30% of account owners are eligible

- More than 50% pass the challenge

- There is no increase in malicious activity

- The load on Facebook support was decreased

Measuring Privacy Interest with Search Queries, presented by Andrew McNamara

Takeaways

Additional reading:

- Americans’ privacy strategies post-Snowden from the Pew Research Center

People overwhelmingly use search queries to find out more about something. A distant second is asking a friend.

Google Trends is one of the few good sources of data about this.

Using a web-based kernel approach, the summaries for the first 100 search results for a given query were collected and filtered for semantically similar content.

What does semantically similar mean?

For example, a query for a private search engine might turn up results for Duck Duck Go, which would be semantically similar to the search query, but it could also turn up results about Gabriel Weinberg, its founder, which would not be semantically similar to the search query.

Tools for observing data flows, presented by Serge Egelman

Egelman (and others) have created a dynamic analysis tool (combined with bespoke network tools) that answers the question: what data do apps collect and where do they send it?

Currently, the tool is being used to fuzz the UI of over 5000 children’s apps for Android.

While Google does require app developers to click through a series of questions about COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) compliance, Egelman found that the majority of these apps were violating the federal law:

- 63% transmit ad identifiers

- 53% transmit hardware identifiers

- 6% transmit personally identifiable information

Egelman contacted the developers in question and found that many don’t fully understand what their third party SDKs are doing. This is problematic, since legally, developers are liable for the violation.

This presentation was the soft launch of the tool, which can be found at AppCensus.mobi. The group hopes to use virtualization in the future to fuzz the apps and offer an API for developers to test their apps for COPPA compliance.

Talks on Attacks and Defense

Can we fight social engineering attacks by social means? Assessing social salience as a means to improve phish detection, presented by James Nicholson

Here is the original paper.

Takeaways

Phishing is a big problem: there were more attacks in the second half of 2016 than in the whole of 2015.

Additional reading:

Raise the Curtains: The Effect of Awareness About Targeting on Consumer Attitudes and Purchase Intentions, presented by Sonam Samat

Here is the original paper.

Study details

This study built a scale to measure opinions toward targeted ads then evaluated how opinions affect purchase intentions.

Takeaways

There is an FTC regulation (note that online advertising is a self-regulating industry) that targeted ads have an icon identifying them as such. Clicking on this icon lets users opt out of targeted advertising, but most users don’t know that and have very different assumptions what the icon and the label ‘AdChoices’ means.

Using chatbots against voice spam: Analyzing Lenny’s effectiveness, presented by Merve Sahin

Here is the original paper.

Study details

Sought to answer the question: Can we automate a solution against voice spammers?

Lenny is a chatbot created by an anonymous person that has had some success, despite not having any speech recognition or AI component and only having 16 audio files as part of his repertoire.

Lenny users would receive a call, and if they identified it as a spam caller, they would the call to Lenny’s chatbot telephony server.

This study transcribed and analyzed 200 voice spam calls received by Lenny uploaded to Youtube.

So how did Lenny do? Data below is per call.

- The average call duration was 10 minutes and 13 seconds

- The average number of conversational exchanges was 58

- The average number of times one of Lenny’s 16 audio recordings was repeated was 1.7.

Lenny was only explicitly called out as a chatbot in 5% of calls.

Notes from conversations over lunch

Additional reading

- The Information Superhighway has become The Information-Tracking Superhighway(https://mascherari.press/the-information-superhighway-has-become-the-information-tracking-superhighway-2/) by Sarah Jamie Lewis

Twitter targeted ad and user data is available to each user

Twitter has recently made a bunch of user privacy changes and made ad data available to users in a PDF. I tried this out myself post-SOUPS, and I found the option by going into Settings > Your Twitter data.

I requested two PDFs, one for the list of 544 advertisers who have categorized me in 2813 “audiences” and one to request all my Twitter data. I believe the first PDF will actually tell me which audiences I belong to. I’ll talk more about this once I receive the list.

OWASP - Open Web Application Security Project

OWASP - Open Web Application Security Project is a professional, global, software security association. They regularly publish a list of the top 10 vulnerabilities on the web. There is a Bay Area meetup chapter that I should check out.

I had already heard of OWASP, in the context of an open-source security scanner called OWASP ZAP that my mentor, Paul Theriault uses as part of his security review work (see my previous blog post).

- WebGoat, DroidGoat and iGoat

Created by OWASP, these are purposely vulnerable applications that allow software developers to improve their security practices through a series of tutorials.

Talks on Privacy

Valuating Friends’ Privacy: Does Anonymity of Sharing Personal Data Matter?, presented by Yu Pu

Here is the original paper.

Study Details

This study looked at how Facebook users value their friends’ data privacy relative to their own in the case of sharing anonymity (i.e. whether or not those friends could find out) and in the case that sharing their friends information had context relevance (the information was actually used by the app).

Takeaways

If a Facebook user installs an app, their friends’ information could be accessed by that app, regardless of whether it is contextually relevant (i.e. the information is actually used by the app).

Most Facebook users would be willing to trade their friends’ data for improved app performance and in general value their friends’ data very low relative to their own.

Self-driving cars and data collection: Privacy perceptions of networked autonomous vehicles, presented by Cara Bloom

Here is the original paper.

Study Details

This study looked at people’s thoughts and concerns around data collection by autonomous vehicles (AVs).

There is concern about AVs because:

- the sensors are mobile

- they collect information in public without people’s consent

- they are owned by a private company (e.g. Uber) whose goal is to monetize the data they collect

- as opposed to surveillance in London where one could assume it’s in the public interest

This study sought to ask the question: What is a reasonable use of data collection for AVs?

- What do people think these cars are capable of (in terms of data collection)?

- How comfortable are they about it?

- Would they want to opt out?

- How much time would they be willing to spend to opt out?

It distinguished between primary and secondary uses of data collected. Primary use means the data is essential for the AV to function safely. Secondary use means the data is not essential.

Note: Time was used as a measure of effort, because it was found to be more evenly valued by people than money (e.g. an affluent person would be willing to spend much more money than others).

Takeaways

More than half of participants were uncomfortable with secondary uses citing that they are not necessary to function and that there is no consent given. If they were comfortable, the top reason cited was the ubiquity of data collection (i.e. smart phones already do much of this).

The most interesting takeaway was how large of an effect priming had on the answer for how long people would spend to opt out:

- Unprimed group: 1-5 minutes

- Primed group: 5-10 minutes In other words, simply raising the questions about privacy related to AVs significantly increased people’s overall concern and willingness to do something about it (at least what they say they would do).

Some participants astutely noted that they would likely have to provide information, such as pictures of their face, to opt out of facial recognition.

Format vs. Content: The Impact of Risk and Presentation on Disclosure Decisions, presented by Sonam Samat

Here is the original paper.

Study Details

Unlike the healthcare and financial industries, the ad industry is self-regulated acting on recommendations made by the FTC.

In the healthcare and financial industries, companies are required to provide consumers notice of how their data is used and the choice to opt out.

This study looked at how two factors influence a user’s decision to share their data:

- Content

- Content refers to the nature of what is being shared and with whom.

- For example, more risk might be perceived in sharing data with an ad company versus a university research group and therefore some people may be less willing to share their data with the former.

- Format

- Format refers to how options are worded.

- For example, it is already known that using a more affirmative tone (allow and accept over deny and prohibit) in privacy policies leads more people to agree to share their data.

Takeaways

Content and format matter, both separately and when taken together: when the risk of sharing data was increased (from research assistants to ad companies to professional network), individuals were more susceptible for format factors (such as whether to allow or prohibit sharing their data.

New Me: Understanding Expert and Non-Expert Perceptions and Usage of the Tor Anonymity Network, presented by Kevin Gallagher

Here is the original paper.

Study Details

Tor is a decentralized anonymity network provided by the nonprofit Tor project.

It works by adding at least three nodes in between the client and the server: an entry, middle and exit node.

This study interviewed 17 Tor users, 11 non-experts and 6 non-experts about their mental model of how Tor works and threat model for what it protects them from. This was in an effort to improve Tor as a product.

Takeaways

Experts had a very complete mental model of how the Tor Network works and saw it as a versatile tool more than just a tool for anonymity (e.g. Tor can be used to access hidden services). They mostly understood the threat model – though some didn’t include the browser as being a part of the threat model (which can leave them open to fingerprinting, for example).

Non-experts generally understood that Tor provided some element of geographic dispersion, but didn’t really understand how it was achieved. Most misunderstood the threat model.

- No mention of decentralized nodes

- No identification of the nodes themselves as a risk One person only used Tor when using credit cards, but this is very risky, because there is no SSL or TLS encryption between the exit node and the web service.

How to improve Tor

Tor ships no-script by default, which was a big problem for many users. Perhaps Tor could vet and whitelist a subset of JavaScript methods?

It is possible for Tor users to view information about each node being used, but it requires active ‘click and seek’. Perhaps make this information more accessible and visible to users.

How to talk to non-experts about threat models

Rather than explain to non-experts everything that Tor does, just explain to them what aspects of their threat model are protected by Tor (and what aren’t).

Privacy Expectations and Preferences in an IoT World, presented by Pardis Emami Naein

Here is the original paper.

Study Details

This talk was about a study looking at people’s comfort levels with sharing certain kinds of data as a part of the Personalized Privacy Assistant Project.

Takeaways

Actual user behavior is often different from self-reported behaviors.

How what I learned improved my ability to contribute to free and open source software

There were many things that I learned that I will be able to apply directly to my Outreachy internship project and beyond:

People want to feel like they are in control of their data. They should be notified what data is collected and why, how long it is kept and given the option to opt out. They should also be given a very clear option to permanently delete their own data.

- We should be sure to notify Lightbeam users what data is collected and how it is used, and give them the option to permanently delete their data at any time in an unambiguous way.

- More generally, users should be given notice in the form of a privacy policy and the option to opt out in any project I work on or contribute to in the future.

App developers are legally liable for meeting federal regulations around data privacy and security such as COPPA compliance in the U.S.

- For Lightbeam and future projects, I must ensure I make the necessary checks to be compliant with this and other regulations – not just in my code but in any code dependecies as well.

Many standardized icons on the web are misunderstood and result in the opposite from safe/desirable behavior:

- TLS indicators like the HTTPS lock icon: this icon indicates connection security, not site safety as many people believe.

- The AdChoices icon: clicking on this icon actually lets users opt out of targeted advertising, it is not an ad company as many people believe.

- In the vast majority of situations, icons alone aren’t enough to tell people what something means. Whether at Mozilla or elsewhere, I will use these as examples where confusion can actually cause people take actions that put their privacy or security at risk. As a developer, I have to work hard to ensure that I and other developers build a UI that makes it clear what taking a certain action does and could potentially do.